More evidence that low-calorie sweeteners are bad for your health

Studies show that artificial sweeteners can raise the risk of hypertension, metabolic syndrome, type 2 diabetes and heart disease, including stroke.

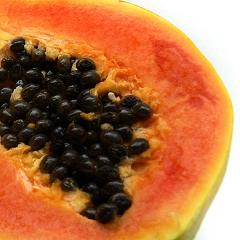

Natural Health News —If you want to boost you intake of carotenoids, new data suggests that you’d be better off eating some papaya than a tomato or a carrot.

All three foods are important dietary sources of beta-carotene and lycopene. But scientists wanted to find out if there was any difference in the bioavailability of carotenoids between them.

This small study, in the British Journal of Nutrition, involved 16 people who randomly assigned to eat meals containing raw carrots, tomatoes and papayas each of which supplied an equal amount of beta-carotene and lycopene.

Carotenoids are lipophilic, that is stored and transported around the body in fats, so the researchers studied the levels of carotenoids found in what are called triglyceride-rich lipoproteins (TRLs), which the body releases after a meal, to assess bioavailability. Results were analysed over 9.5 hours after test meal consumption.

The bioavailability of beta-carotene from papayas was approximately 3 times higher than that from carrots and tomatoes, whereas differences in the bioavailability of beta-carotene from carrots and tomatoes were insignificant.

Retinyl esters, a form of vitamin A which the body produces from carotenoids, appeared in the TRLs at a significantly higher concentration after the consumption of the papaya test meal. Similarly, lycopene was approximately 2.6 times more bioavailable from papayas than from tomatoes.

In addition, the bioavailability of beta-cryptoxanthin from papayas was shown to be 2.9 and 2.3 times higher than that of the other papaya carotenoids beta-carotene and lycopene, respectively.

Understanding carotenoids

Two forms of vitamin A are available in the human diet: preformed vitamin A (retinol and its esterified form, retinyl ester) and provitamin A carotenoids. We get preformed vitamin A from animal source foods such as dairy products, fish and meat (especially liver).

Of the provitamin A carotenoids beta-carotene is the most important. Other provitamin A carotenoids are alpha-carotene and beta-cryptoxanthin. The body converts these plant pigments into vitamin A. Other carotenoids found in food, such as lycopene, lutein, and zeaxanthin, are not converted into vitamin A. While beta-carotene in itself is not an essential nutrient, vitamin A is. We all need it for healthy skin and mucus membranes, our immune system as well as good eye health and vision.

The authors, with an eye on improving vitamin A status in some of the world’s poorest countries, conclude “papaya was shown to provide highly bioavailable beta-carotene, beta-cryptoxanthin and lycopene and may represent a readily available dietary source of provitamin A for reducing the world’s incidence of vitamin A deficiencies in many subtropical and tropical developing countries”.

The finding is particularly important since developing countries are coming under increasing pressure to develop a variety of genetically modified vitamin A-containing rice called ‘Golden Rice’ which though unregulated and not commercially available is being touted as a future cure for blindness associated with vitamin A deficiency. Unlike Golden Rice, papayas are widely available and affordable to people in these countries.

But of course, the research also has implications for people in developed countries whose diets may be suboptimal. Adults need around 3000 mcg – or 10,000IU – RAE (retinol activity equivalents) of vitamin A from food daily. Typically 6μg of dietary beta-carotene supplies the equivalent of 1μg of retinol, or 1 RAE. If you take supplements these should indicate what percentage comes from preformed vitamin A and what percentage comes in the form of provitamin A.

Please subscribe me to your newsletter mailing list. I have read the

privacy statement